In August 2013, a Cornell lab accident left a chemistry graduate student severely injured. For many, the Cornell administration’s and graduate workers’ responses dramatized both graduate workers’ lack of workplace protections and the potential of graduate organizing.

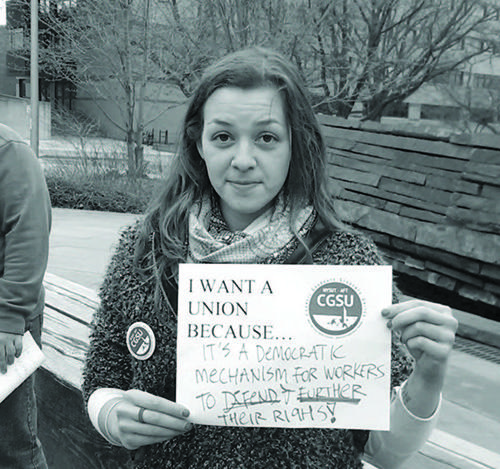

Cornell Graduate Students United (CGSU) emerged in March 2014 with a commitment to grassroots organizing and democratic practices. By September 2014, CGSU was a small but fully functioning graduate student union with its own organizing structure, constitution, and bylaws. It had over 150 members, about 3% of the graduate student body at that time. As membership numbers rose, the limitations of CGSU’s human, financial, and legal resources grew more plain, and CGSU began then to seriously discuss affiliation with national labor organizations.

In a September 2015 membership- wide vote, CGSU chose to affiliate with American Federation of Teachers (AFT-NYSUT). The decision around affiliation was made was made because, unlike many other national unions, AFT explicitly recognized CGSU as an autonomous grassroots body with its own democratic organizing structure and decision- making processes.

AFT Suspends Democracy

But soon after affiliation with AFT-NYSUT, it became clear that CGSU’s autonomy and democratic functioning would be suspended for the next year and a half. This was justified in the name of emergency, an intensive recognition election campaign.

In internal union discussions, democratic practices that had, in fact, been terminated by the new rules were increasingly framed as attainable only by way of a campaign victory. In short: from its beginning until the present, the story of CGSU has been one of the orchestrated collapse of its democratic structures and practices. This loss of any real connection with its members was the reason that CGSU would ultimately lose its recognition election.

The mechanisms of this collapse were instructive: while polarization grew among CGSU’s more active membership, disaffection grew among CGSU’s rank and file. Both the polarization among the active and the divestment by passive membership left CGSU vulnerable to AFT-NYSUT control, which, in a vicious cycle, only compounded the disintegration of internal democratic structures.

The polarization among mobilized members was largely around AFT-NYSUT’s organizing model, which actively limits the flow of information between members and their union. Among the union’s most active members, critical deliberation degenerated. Across campus, graduates campus-wide reported feeling “harassed,” “instrumentalized,” and “deceived” by CGSU’s organizing campaign. That workers began to distance themselves from union affairs out of distaste for what was happening ultimately aided AFT-NYSUT’s goal of wrenching control of the union from the workers themselves.

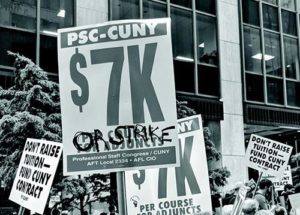

When the votes for the recognition came in, the results were 856 for CGSU, 919 against. Another 81 ballots were challenged by either Cornell or CGSU/AFT-NYSUT. Because the number of challenged ballots there were never enough votes for CGSU to cover their 63-vote deficit, the election remained officially “inconclusive” until those ballots were processed. This was to both AFT-NYSUT’s and Cornell’s liking. Cornell, of course, would prefer to forget about graduate unionization efforts altogether.

For its part, AFT-NYSUT was similarly eager to bury its embarrassing loss of a million- dollar campaign on an avowedly liberal campus in the era of #resistance and rising grad unionization. These interests prevailed over CGSU’s when, in the aftermath of the election, a small number of active CGSU members “authorized” AFT-NYSUT to enter negotiations with Cornell’s administration. CGSU’s general membership not only played no part in this decision, but were unaware of even the existence of these negotiations for the five months they were conducted.

During this time, union-wide activities and agency were effectively “on pause.” The opportunity to rebuild, to work through the experience of a passionate campaign, to reconnect with the rank and file, to learn from mistakes— in short, to face reality—was, in this period, squandered. The fruitless negotiations ended. CGSU filed three complaints against Cornell with the American Arbitration Association.

The arbitrator’s decision—to certify the election results, and to affirm just one of CGSU’s complaints—came over a year after the 2017 recognition election. The collapse of the bargaining unit’s mobilization was demonstrated at roughly the same time, in the outcome of CGSU’s annual Steering Committee election. Of the Steering Committee’s thirteen seats, only two had more than one candidate running to fill them, and less than 60 out of CGSU’s 1500 members took the trouble to vote online.

Lessons from the Aftermath

What can be learned from the collapse of CGSU? One lesson: building a strong union with an engaged rank-and-file, and winning a recognition election are two separate goals. CGSU’s mistake was to conflate the two, and to distance itself from healthy democratic governance for the sake of chasing a recognition vote win.

The lost election was a direct consequence of this pyrrhic sacrifice, but it was not the worst one. The worst consequence was the change in the culture and meaning of unionization.

Our union began as a space of workers’ empowerment, political education, and deliberation, mobilized by an approach to social justice that aimed beyond the securing of basic rights. As CGSU compromised its democratic functioning, the union transformed into precisely what it had been formed to fight: yet another top-down and opaque institution.

This transactional understanding of unionism has kept CGSU from ever seriously engaging with its rank and file, facing its own mistakes, or evoking an emancipatory politics ever more deeply than a “solidarity!” facebook post. At the other end of its futile compromise, CGSU’s politics have become gestural, contenting itself with periodically calling- out of Cornell University for what it says or doesn’t say or does or doesn’t do, but never for what it is.

The critique of the institution itself— a corporation with a systemically exploitive relations to area workers, resources, and communities; a leading institution of class warfare; an integral, and foundationally racist and sexist cog in the American war machine— has been lost. In short, the transactional unionism that operates only with an eye to a “yes” recognition vote produces an uncritical, catch-all politics.

This politics is incapable of analysis or critique, much less operating meaningfully to dismantle the violence at the heart of the institution. The punchline for our union is that there’s nothing left to lose. Spooked by the threat that the existing NLRB decision granting grad workers at private universities the right to unionize will be overturned, national labor federations have gone into a winter sleep on private university campuses.

Perhaps counterintuitively, this is not bad news for unionization campaigns that have been run into the ground by top-down union procedures. CGSU finally has some space for rebuilding and reinvention, for honesty and creativity, and for the first time in a long time, AFT-NYSUT isn’t dominating the conversation. CGSU has so far made little of these opportunities, and may well continue to decline.

Meanwhile, the need and potential for democratic and grassroots unionization still urgently exists at Cornell. The task to rebuilding now is the same as it has ever been. Graduate workers must build democracy not through its obverse, but through democracy itself.